A story

about a human being's affinity to Nature and the meaning of living and dying in

search of her secrets.

By Carlos Rivero Blanco

This

brief essay is dedicated to the memory of Andy Field, to the Rancho Grande

cloud Forest, a place I admire as being the essence of nature itself, and to

the Henri Pittier National Park, where I was introduced to the secret life of

the jungle when I was still very young.

THE FOREST

The fog, still thick and wet, prevented us from

seeing the sunrise. It was still early and the outlines of the jungle barely

sketched a subtle design on the still dark background. Relative humidity was

100 percent, and ... Why shouldn't it be? After all it was the month of August,

during the wet season, when the cloud forest shows off to the visitor its

maximum splendor. Because of this, my son and I had climbed the mountain and,

at the break of day we wanted to feel it as our own.

The

forest, all disheveled, as though just getting up, showed its profile against a

misty background. It was the eternal outline: dark, thick trunks joined

together by an irregular network of the silhouettes of leaves and vines; palm

trees with slender trunks and long stemmed ferns, their heads drooping over

themselves and over us their symmetric filigree-like leaves. It reminded me of

the paper dolls cut out by children which, when opened out, repeat an endless

pattern of figures joined together.

The

jungle profile did not remain still. Gently, a soft breeze moved the white mass

of clouds which enveloped the mountain. On passing, it would stir the leaves,

which would vibrate before our eyes. It did not remain silent, either, for the

dew condensed on the leaves, would keep falling, producing a constant rustle

over the layer of dead foliage covering the ground.

With a

small effort, in the increasing and more revealing daylight, you could follow

the course of one of these droplets. Looking at the branches overhead, you

could catch a particular drop on its first motion. It was like a slow, lazy

"dropping down", almost unwilling, letting the wind and gravity make

all the effort.

The drop,

with all its sluggishness, would take its first jump over the void falling on a

broad, thick leaf of climbing malanga, the kind that so profusely cover the

tree trunks in these cloud forests. Surprisingly, our dewdrop turned into four

or five, as the denticulated malanga leaf, on impact, let loose the drops that

had been forming on the ends of its long fingers and were merely waiting for a

small push.

We could

continue to follow only one of these droplets, which fell into a small puddle

formed in the middle of one of the "tree pineapples" or bromelias,

the flashy plants with spiked and star-like leaves forming large tufts over the

wet branches in the darkest spots of the jungle. It was the drop that

overflowed the puddle and also scared away a tiny frog which had spent the

night there. The frog, as well as another drop, fell on a giant taro leaf, very

close to the ground. The tip of the taro leaf then let a small quantity of

water run on the jungle floor, and the frog quickly fled from our sight.

Gradually,

the sounds of the jungle kept changing. The twittering of the crickets and

other night insects was stilled and, simultaneously, on the distance we could

hear the low guttural drone, revealing the presence of the brown and red

howling monkeys. The first birds made swift passages through the foliage, which

now delineated the clear outlines of a jungle, over a nebulous background of

water vapor condensed to form a dense mist. A large bird, the olive sparrow,

was trying to catch a butterfly resting on a lichen covered trunk of a trumpet wood

tree on the edge of the ravine. A querrequerre, that beautiful yellow breasted,

green-winged, long-necked and blue-headed bird, also jumped from branch to

branch in search of an unwary insect.

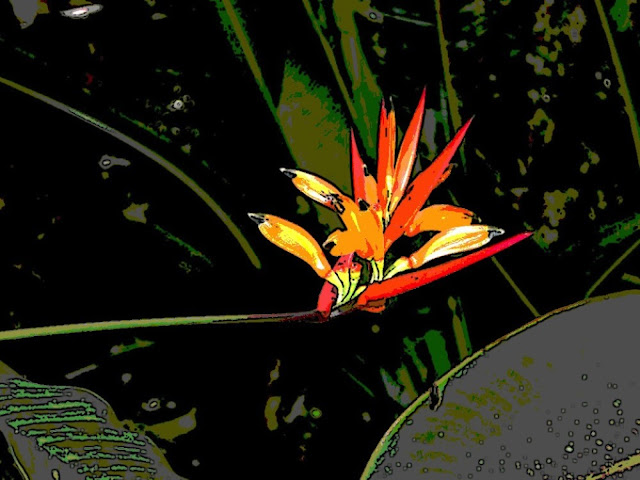

By

daylight, though still shrouded in clouds, we saw the jungle at its full

splendor. We could see and admire the soft cushions of moss covering the tree

trunks, the branches and leaf patterns of the plants closest to us. A few were

in bloom, such as the casupo, whose inflorescence is enclosed by orange-colored

bracts and sometimes show small, yellow corollas, or carmine-red tubular ones,

so small that only the thin beak and long tongue of the hummingbird can extract

its nectar. Thus morning light brought out the colors that imparted variety on

the jungle.

Meanwhile,

on a leaf the size of a human hand, a spider was examining the web it had

delicately spun over it in order to trap its food. It had been somewhat damaged

by the prior evenings rain, and the spider was busily repairing it.

THE GIANTS

Drops

were still falling from the roof of the jungle and my son, still intent on

following their downward course, was looking up, and suddenly exclaimed, quite

impressed:

"How

big! How tall!" He was referring to the giant trees before and above him.

They were really colossal, their tabular roots looked like triangular walls

that seemed to support the weight of the massive trunks. You could scarcely see

the branches, so very high up, and far away from us, distant even from the tops

of the other jungle trees.

"Gosh!

How big they are! Makes you feel so small!", he exclaimed amazed by the

hugeness of those jungle giants, undoubtedly impressed by the portly majesty of

the growth projecting itself far above the roof of the cloud forest.

This

scene reminded me of a similar experience I had several years ago, when I first

saw a "Cucharón" or "Niño", the tallest tree in the cloud

forest of the Coastal Mountain Range. Those awe-inspiring specimens reached a

height of more than 170 ft., and formed the layer of emerging stratum on these

mountain jungles. I don't recall exactly the place, though it is not far from

here. What I do remember is that it was a group of five or six immense and

impressive trees.

The tops

of these giants showed digitated leaves, like hands with extended fingers. The

only remarkable thing about it is that the "fingers" are seven. The

petioles are long and thin, hard to appreciate from the floor of the jungle.

The large white flowers are barely discernible from a distance. The fruit is a

sort of large, chocolate colored capsule, which on maturing sheds its walls,

drops its seeds to the ground from a hanging bag which swings with the wind like

a pendulum.

The

red-brown seeds, the size of the end bone of your thumb, show a wing-like

flatness on one end. It looks like a half of an airplane propeller which, on

falling starts turning and slowly flying away from the mother tree. Its scientific

name Gyranthera caribensis (from "Gira" = to turn and

"anthera" = stamens) is quite descriptive of the way the flower

stamens are entwined.

Undoubtedly,

these trees impress everybody. Their size is something that definitely attracts

attention of whoever ventures into the heart of the places and can look up

towards the ceiling of the cloud forest to admire these wonders of nature.

ENTER ANDY

When dawn

at last appeared, the gray outline of an impressive, old and partly built

structure, showed itself amidst the vegetation. It was a steel and concrete

mass, with a sort of dual personality. On the one hand it has a facade with

giant glass windows, inviting the sky to come within, and conversely, it showed

three unfinished stories, with dark and lugubrious cubicles whose

moisture-covered walls sheltered a diversity of jungle creatures.

I had

always been impressed by those compartments. In them I had observed the myriads

of bats that slept during the day between the walls and ceiling, as well as

tiny swallows that made their nests in little holes and cracks. A few geckos

had made the walls into their permanent home, which afforded them shelter as

well as food, as many insects swarm in those nooks. From time to time, a

whitish tree frog would appear, and clinging to the moss-covered walls, would

see time pass by on a rainy day.

The sight

of these small rooms brought us back several years on the history of Venezuela.

A long time ago, in this place then called Rancho Grande, near the Portachuelo

pass, there was a very rustic inn, which offered shelter and provisions to the

mule drivers who plied their trade between Maracay and Ocumare, on the Coast.

By 1915 many bridges had been erected, thus permitting the passing of

horse-drawn carts. By 1933, all was radically changed when Juan Vicente Gómez,

the dictator, had a wider road built, over which automobiles could travel.

During

those years, the inn was torn down and, on its site, Gomez ordered the building

of a great 120-room hotel. When the dictator died in 1935, the Rancho Grande

Hotel remained unfinished, its main structure only partly built. In 1937, the

Venezuelan government decreed the protection of these jungles, establishing the

Aragua National Park, which later was renamed "Henry Pittier Park" in

honor of the famous botanist.

As time

went on, the building was transformed into a science lab. Sitting in the middle

of the cloud forest at Henri Pittier National Park, it was used as a shelter

for researchers of the flora and fauna of the region. William Beebe, one of the world’s most

celebrated zoologists and scientific minds, lived there between 1945 and 1946,

and for almost a year he studied the lives of the jungle creatures. Many more

came later, some from abroad as well as many young Venezuelan researchers who

were gradually being educated in our universities. After a time, Rancho Grande

became world-famous as a place for studies, and attracted many naturalists to

its soil.

A few

years ago, on the corridors of the mysterious building, I met someone who

seemed to be one of the many naturalists I had encountered at Rancho Grande.

He was a

young man, about 20 years old, of British origin. Of slight build, blond hair,

bluish eyes, the cloud forest exerted a great fascination on him because of its

life diversity, and the surrounding tropical atmosphere were so different from

the lugubrious English fog.

Andy was

a botany student, and precisely that was what had brought him to Rancho Grande.

To study the plants of the forest and be able to understand and explain some of

their ecological relations was his most cherished goal. Some three years of

research in these places would enable him to gather sufficient data to write

his thesis.

MEETING THE GIANTS

The

jungle surrounding the building at Rancho Grande was truly exuberant. Its

flowering composition varied a lot, depending on how far or how near you got to

the Portachuelo pass. Close to it, the moisture condensing on the plants was

notorious, coming from the clouds pushed by the trade winds toward the mountain,

and managing to get across the gorge, or mountain pass and cover the jungle

with its grayish presence. As you got farther away from the pass, there was

less humidity condensation and the plants were of different species, which

tolerated a somewhat drier environment.

In the

more humidity-exposed places there was an amazing profusion of epiphytic plants

(that is, plants living on other plants) such as malangas, vines, lianas,

lichens, mushrooms, orchids and bromeliads. In less humid places the epiphytes

were scarcer but it was no less tangled and sometimes confusing. It gave the

impression of a large shroud covering everything, while at the same time giving

you a visual sensation of the complicated relationships between the plants and

other living organisms of the forest.

Walking

there was difficult, through narrow footpaths and sometimes over the delicate

shoots and sprouts of the woods scions of the great trees, which were waiting

there for an opening in the tree tops which would give them a chance to have

more light and thus grow faster and eventually reach the jungle roof. Many

times I explored with my pupils those inner forest footpaths. But our progress

was slowed and made more careful by some red and yellow strings, laid out in

squares by Andy, to mark off an area of about two and a half acres in that part

of the jungle flanking the mountain behind the Rancho Grande building. That

fine network of colored strings enabled the researcher to measure exactly the

position of each plant on a squared plane, and transfer the data to a squared

paper chart that would show spatial distribution of each species and the

relationship between diverse species.

In the

course of time, and perhaps because of so much looking upward, Andy's

fascination with the cloud forest became centered on one particular, very

prominent, element, but nevertheless very distant, that very much attracted his

attention: the giants of the forest, the "Cucharones" or

"Niños", those trees of colossal dimensions that break out above the

jungle's roof as a sort of "horizon watchers".

This is

how Andy and the giants met and how their relationship began: he in the role of

the typical researcher, fascinated and mesmerized by his subject of study, and

they, as living beings, endowed with the most interesting natural gifts and

faculties, worthy of being discovered and recorded by whoever could reach their

heights.

From then

on, the squared terrain marked off by red and yellow strings became a map of

the distribution of the giant trees. Now he had to find a way to somehow climb

to their highest point. It was no longer enough to look at their tops from the

ground up, from a distance of 100 to 170 feet. He had to investigate what their

flower buds and blooms looked like, what sort of animal species pollinated them

and how they were fertilized, how their fruits grew, how their seeds were

dispersed, and many other things.

That is

how our friend learned to climb and come down from the giants, using the

special gear and nylon ropes employed by mountain climbers. Thus it was that

Andy managed to satisfy that dream of all children of having their very own

"tree house", or at least a sort of wooden platform from where he

could be "master" of the jungle's roof.

There he

used to spend long hours watching every sort of creature that approached

"his" trees. From close contact, he familiarized himself with the

giants' "life styles", to put it that way, and probably learned the

time of the year when they put out their blooms, or fruits, or let their seeds

drop. He used to spend the nights there, specially during the flowering season

and in pitch darkness, surrounded by the chirping of the hundreds of insects

forming the nightly jungle orchestra, and the choirs of the tree frogs. Andy

documented in minute detail the nightly visits of the long tongued bats, the

perfectly adapted pollinizers of the giants' flowers.

ANDY, THE GOBLIN

It was

almost total darkness, except for the small hand flashlights that allowed us to

see the creepers and vines obstructing the footpath. It was a dark night in

May, during the rainy season, when, accompanied by some twenty of my pupils, we

ventured out with Andy to visit his favorite giants.

In our

field excursions I used to visit the interior of the jungle at night and, once

we found a place where we could sit comfortably, all lights would be

extinguished so that we could experiment total darkness for about half an hour.

The only lights visible in that environment were those of the fireflies or the

small water spiders, which shone as tiny jewels on the stones of the brooks.

After

walking for quite a stretch, we climbed down a side of the mountain, and

constantly slipping over the wet dry leaves we reached the foot of a clump of

giant trees, on one of which Andy had built a platform. There he told us about

his experiences as a researcher and spoke about the biological marvel that were

these trees. Then we extinguished our flashlights and in the most complete

darkness enjoyed our silence and the sounds and melodies of the nightly jungle

creatures.

Andy's

stay in this nook of the woods was going on three years. He lived on the roof

of the old building, with the small amount of money he received from teaching

English lessons in Maracay, and he used to spend some time at the home of his

friend Carlos Bordón, an engineer, a dedicated student of insect life who

discussed about science and conservation with the British young man.

Andy had

been very active in making the jungle and its secrets known to others. Whenever

we talked he expressed his concern about the lack of interest that city

dwellers had in the cloud forest. He said his countrymen did not have the

privilege of having that natural wonder so near-by, and that the people here

should be made conscious of it, and that in order for the forest to be

protected it should first be known and appreciated.

His thin

figure, an eccentric researcher, interned in the jungle over long periods of

time, living alone on top of a ghostly building, gave Andi’s personality a most

peculiar air. People who knew him eventually came to think and talk of him as

"The Goblin of Rancho Grande".

His

anxiety and concern finally reached the Aragua Conservation Society. His

eagerness to build an observation footpath leading park visitors to the place

where the giant trees grow was the crowning of his research efforts. For months

he worked on such a project, backed by some of the young people in the Society,

who actually helped in the building of the interpretive trail which led

visitors to his trees.

THE GOBLIN BECOMES A SEED

The trail

to the Niños or Cucharones was half finished when I last visited it. I walked

the route with my pupils while "the Goblin" explained to us how the

giants succeeded each other. The seeds, tumbling in the air, descended slowly

from on high, flying away from the mother tree to fall on the floor of the

jungle as far as possible from another of its own species. The oldest

individuals, when they died and fell down, would make large clearings in the

woods, their immense weight bringing down other smaller trees.

When

additional light was thus admitted to the depths of the jungle, the young

saplings waiting for a chance to grow, would succeed their parents, and would

once again close the jungle roof with their tops. Occasionally, Andy would

point out one of the scions of the giants which was waiting its turn to begin

growing.

He

specially called my attention to several young trees growing directly on the

stilts of the tubular roots or buttresses. They were sort of vegetative

children, that would grow rapidly if the huge tree mass which fed them with its

own sap would ever tumble down and let some sunlight in. It was difficult to

make Andy speak on any subject other than his friends, the tallest living

beings in the cloud forest.

The last

time I saw the young Englishman was when he brought me some fruit and seeds to

photograph for him. His camera had become rusty from overexposure to the

mountain high humidity. It was very important to document with clear pictures

the form and seed-dispersing mechanism. Showing off his knowledge, he explained

to me just exactly how it worked.

It all

appeared to be so finely designed by Nature: a large fruit, a capsule whose

cover dries up and falls off. This causes some thin and slender sacs full of

seed, to hang suspended like so many pendulums, exposed to the wind at a great

height. The seeds start dropping from the sacs, slowly gyrating until they

reach the jungle floor, where they will try to recommence the life cycle of the

species.

Andy was

euphoric. The moment when his project would come to an end and he would be

returning to England was very close. He had great plans in mind, one of them to

come back and see his giants, when he made some money and could travel again.

I was

astonished as I red the sad news. A month later, a somewhat imprecise newspaper

account told of the death of a young Englishman who had been researching the

life of the plants on the mountains at Pittier National Park.

Andy had

fallen from the top of one of his giants. So much had he harmonized with them

that he had become one of their seeds; like them, he had gyrated in the air, to

plant himself beneath the layer of dead leaves and humid earth, as a message of

love to Nature and an example of dedication to the study of the living beings

of the cloud forest. Strange as it seems, his remembrance took root there,

forever, beside his most beloved friends.

ANDY THE GOBLIN, IS NOW A GIANT

Today,

while accompanied by my son I admire those three huge trees, real wonders of

nature, I realize time has passed and I evoke the memory of my friend. I

believe it is a symbol, an example, for any nature lover.

The young

researcher's audacious thirst for knowledge about the lives of the giants; his

intimate relationship with them and their ways of life; his teacher's attitude

in showing off his trees to anyone who came to look at the cloud forest and the

fact that he dedicated his life to knowing them better, all make us see Andy as

one more tree in the forest.

That is

why I believe Andy is a giant: a symbol of unity between man and the cloud

forest; an important link having much meaning for those who believe it is a

noble thing to learn about and protect our natural environment.

Perhaps

those drops of water we saw this morning falling from on high, are the tears

shed by the great trees in an effort to water with them the roots of their

friend, to make him become one more of the giants of the cloud forest.

THE END? or,... perhaps not yet!

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario